I’m a coach. I’m trained according to the standards of the International Coaching Federation and I ascribe to the profession’s ethical standards. The job description is to help people:

- Understand their situation

- Take responsibility for solutions

- Commit to action that achieves their goals and growth

But you don’t need to be a coach to do these things. You can always do coaching, regardless of your role. Whether you’re a leader, an entrepreneur, a knowledge worker—heck, a functioning human being—there is much to be gained by adopting a coaching mindset.

The best coaches listen actively. They give their clients their full, undivided attention. They’re supportive. They challenge. They create a space of safety and trust where deep insights can be uncovered and growth can occur. They stick to their word. They ask uncomfortable questions, and they’re comfortable with silence. They believe in their client’s potential, and they do everything they can to help the client to find and realize that potential, too.

These are the hallmarks of the coaching profession. But in what job are those characteristics not aspirational?

A recurring theme when reading about iconic figures from the past and present is their coaching mindset. Creative pioneers, fearless leaders, even world-class physicians—so many have exhibited coach-like behaviors.

The world’s greatest editor was one such man.

The unshaken friend

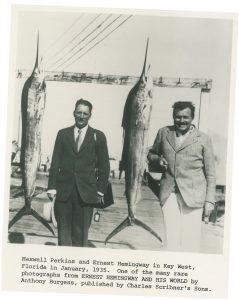

Maxwell Perkins was an unassuming character early in his career. He started out as a hard-working reporter, but soon enough scored a job as an editor at the legendary publishing house Scribner’s.

Perkins’ client list eventually became a “who’s who” of twentieth century literary talent. Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe…the list goes on. All became clients of Perkins. And all loved the man, deeply appreciating the work he did. It’s been said that Perkins has received more book dedications and acknowledgements than any other person in history.

How did Perkins manage these remarkable feats? The short answer is that he was a coach at heart.

He believed in the author’s potential.

“The source of a book must be the author,” Perkins claimed. “You can only help the author to produce what he has in his compass.”

Much of Perkins’ success owed to the fact that he took chances on authors who were turned down by other publishers. He found diamonds in the rough and polished them to their full potential.

“Perkins has the intangible faculty,” said his client Marcia Davenport, “of giving you confidence in yourself and the book you are writing. “

He didn’t order authors what to do.

As Malcolm Cowley wrote in an endearing New Yorker profile in 1944, “When an author is sure about what he is trying to do, Perkins doesn’t make or suggest any revisions, and the manuscript goes to the printer without so much as a shifted comma. This happens even when commas ought to be shifted, for Perkins has no interest in what he regards as unimportant details.”

His clients agreed. “He never tells you what to do,” claimed author Roger Burlingame. “Instead, he suggests to you, in an extraordinarily inarticulate fashion, what you want to do yourself.”

When required, he provided humbly articulated suggestions.

At the height of her powers, author Marcia Davenport found herself stuck in a rut. Perkins fine-combed the manuscript she was working on, and came back to her with numerous suggestions. These were framed as questions, not demands.

“Couldn’t all this be brought into unity by changing the dates and relating one thing to another?” he wrote to Davenport. “It could begin with the phrase…,” he continued. Suggestions were always framed as possibilities and experiments, not demands or irrefutable truths.

He thrived in helping his authors to see clearly through their emotional and professional turmoil.

“A big, long manuscript full of agony and confusion—that’s Max’s dish,” one author said of Perkins.

“What you get from him isn’t expressed in words,” said Davenport. “You might call it a tacit exchange of ideas. Let’s say that you’re working on a novel and find that everything is at a dead end. You go to see Max late one afternoon and he takes you out for a drink. You sit and talk there for an hour or so in a disjointed fashion, with long pauses, and by next morning you go back to work with all your questions answered and a perfectly clear vision of what you are trying to do.”

That unexpected, but oh-so-welcome clarity was a Perkins trademark.

He was always on the author’s team.

This wasn’t just something that Perkins claimed. The language he used conveyed unwavering team affiliation with the author. He wrote to Davenport: “We must somehow bring the underlying scheme or pattern of the book into emphasis, so that the reader will be able to see the forest in spite of so many trees. And that will mean reducing the number of trees if we can possibly manage it.”

There was no “you must”. It was always “we can”.

He challenged his authors with piercing insights and perceptions.

Thomas Wolfe was a rebel. He had a habit of scowling at anyone he found disagreeable at parties and other social gatherings. After one particularly nasty such episode, Perkins told him, “You don’t really hate those people. You hate yourself because your work is going badly.”

Perkins wasn’t afraid of saying what needed to be said, no matter how uncomfortable it was to hear. And because it was so uncomfortable, it provided a new perspective to his clients that helped them to change either their work or themselves for the better.

Challenging. Listening. Supporting. Encouraging. Pinpointing. Creating space. Seeing clearly and helping to see clear. These are all core tenants of coaching. And these are all the skills that made Perkins the world’s greatest editor.

The point is not that everyone needs to become a certified coach. The point is merely that adopting a coaching mindset can be beneficial for anyone. Supporting, encouraging and challenging people to grow are all characteristics to strive for, regardless of one’s occupation.

The value of Perkins’ coaching behaviors was not lost of the world nor his clients. When Thomas Wolfe’s Of Time and the River was published 1935 after monumental struggles, it contained the following dedication:

“To Maxwell Evarts Perkins, a great editor and a brave and honest man, who stuck to the writer of this book through times of bitter hopelessness and doubt and would not let him give in to his own despair, a work to be known as “Of Time and the River” is dedicated with the hope that all of it may be in some way worthy of the loyal devotion and the patient care which a dauntless and unshaken friend has given to each part of it, and without which none of it could have been written.”

Sticking through times of bitter hopelessness and doubt. Providing loyal devotion and patient care. And being an unshaken friend. All are virtues to aspire to and live by, whether you’re a coach, an editor…or just a good-old human being.